Gibbs sampling

Abstract

This article provides the recipes, simple Python codes and mathematical proof to the most basic form of Gibbs sampling.

What is Gibbs sampling?

Gibbs sampling is a method to generate samples from a multivariant distribution P(x1,x2,…,xd) using only conditional distributions P(x1|x2…xd), P(x2|x1,x3…xd) and so on. It is used when the original distribution is hard to calculate but the conditional distributions are available.

How does it work?

Procedure

Starting with a sample x=(x1,x2…xd), to generate a new sample y=(y1,y2…yd), do the following

- Sample y1 from P(y1|x2,x3…xd).

- Sample y2 from P(y2|y1,x3…xd).

- Sample y3 from P(y3|y1,y2,x4…xd)

- … and so on. The last term is sampling yd from P(yd|y1,y2…yd−1).

- Now we have the new sample y. Repeat for the next sample.

Note that the value of a new sample depends only on the the previous one, and not the one before, Gibbs sampling belongs to a class of methods called Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC).

Example

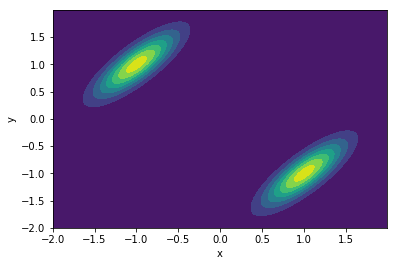

Consider a mixture of two 2-dimensional normal distribution below with joint distribution P(x,y)=12(N(μ1,cov1)+N(μ2,cov2)).

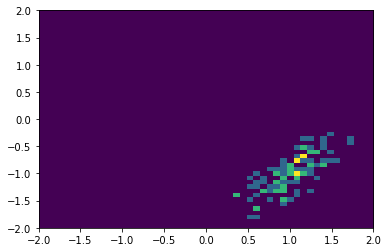

We can use the procedure above to to generate samples using only the conditional distribution P(x|y) and P(y|x). The sample chain could initially be trapped in one local distribution:

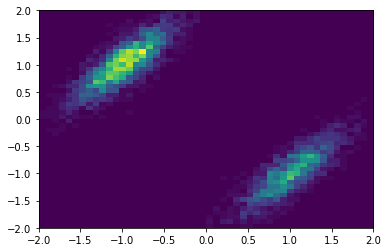

But if enough number of points are sampled, the original distribution is recovered:

The codes that generate this example can be found here.

Why does it work?

This section outlines the proof of Gibbs sampling. I mostly follow MIT 14.384 Time Series Analysis, Lectures 25 and 26.

Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC)

Gibbs sampling generates a Markov chain. That’s obvious because the series X(1), X(2), X(3) … depends only on the previous value. An important concept to understand is the transition Probability P(x,y), the probability of generating sample y from the previous sample x.

Suppose we want to sample a distribution π(x), we want to generate samples in a way that the new sample still follows distribution π(x). Mathematically, for transition probability P(x,y), the probability measure π(x) is invariant if

π(y)=∫P(x,y)π(x)dxand the transition probability is

- irreducible (i.e. any point can reach any other points)

- aperiodic

The MCMC problem is to find a transition probability P(x,y) such that π(x) is invariant.

Proof

The procedure of Gibbs sampling outlined previously can be written as a transition probability

P(x,y)=π(y1|x2,x3,..,xd)π(y2|y1,x3,..,xd)...π(yd|y1,y2,..,yd−1)=∏kπ(yk|y1...yk−1,xk+1...xd)Let π(x) be the distribution we want to sample from. We need to show π(x) is invariant under this transition, i.e.

∫P(x,y)π(x)dx=π(y)In other words, if we follow P(x,y) to get new sample y based on the previous sample x, and repeat this process over and over again, we stay in the same distribution π(x).

Since we need to integrate over x, the first thing is to rewrite P(x,y) using Bayes rule so that there’s no conditional on x. Bayes rule is

P(A|B)P(B)=P(B|A)P(A)or if there’s always a conditional on C:

P(A|B,C)P(B|C)=P(B|A,C)P(A|C)Using

A=ykB=xk+1,...,xdC=y1,..,yk−1We get

π(yk|y1...yk−1,xk+1...xd)=π(xk+1,...,xd|y1,..,yk)π(yk|y1,..,yk−1)π(xk+1,...,xd|y1,..,yk−1)Substituting this to Eq.(4), and noticing that π(yk|y1,..,yk−1) does not depend on the integrating variable x,

∫P(x,y)π(x)dx=∏kπ(yk|y1,..,yk−1)∫∏kπ(xk+1,...,xd|y1,..,yk)π(xk+1,...,xd|y1,..,yk−1)π(x)dxThe first product

∏kπ(yk|y1,..,yk−1)=π(y)because

π(y)=π(y1,y2,..,yd)=π(yd|y1,..,yd−1)π(y1,..,yd−1)=π(yd|y1,..,yd−1)π(yd−1|y1,..,yd−2)π(y1,..,yd−2)... and so onSo we have

∫P(x,y)π(x)dx=π(y)∫∏kπ(xk+1,...,xd|y1,..,yk)π(xk+1,...,xd|y1,..,yk−1)π(x)dxWe need to show the integral on the right hand side to be exactly 1.

We start by writing out the terms explicitly and use π(x1,..xd)=π(x1|x2…xd)π(x2…xd),

∫∏kπ(xk+1,...,xd|y1,..,yk)π(xk+1,...,xd|y1,..,yk−1)π(x)dx=∫π(x2...xd|y1)π(x2...xd)π(x3...xd|y1,y2)π(x3...xd|y1)...π(x1|x2...xd)π(x2...xd)dx1dx2...dxdThe only term that depends on x1 is π(x1|x2…xd) and it is integrated out to be 1. The integral becomes

=∫π(x2...xd|y1)π(x3...xd|y1)π(x3...xd|y1,y2)π(x4...xd|y1,y2)...π(xd|y1...yd−1)dx2...dxdTurning each fraction into a conditional probability

π(x2...xd|y1)π(x3...xd|y1)=π(x2|x3..xd,y1)and so on. The integral becomes

=∫π(x2|x3..xd,y1)π(x3|x4..xd,y1,y2)...π(xd|y1...yd−1)dx2...dxdOnly the first term depends on x2 and it is integrated out to be 1. After that, only the leading term depends on x3 and it is integrated out to be 1 and so on. Therefore the whole integral is 1 resulting in

∫P(x,y)π(x)dx=π(y)So the transition probability from Gibbs sampling is invariant. If we sample according to the Gibbs scheme, we can get unbiased samples of π(x).